Why F# is the best enterprise language

Just to be clear, I’m only going to be talking about so-called “enterprise development”. I’m not claiming that F# is the best for systems programming, or games development, or hobby projects. What’s appropriate for one kind of development objective may well be inappropriate for another. Enterprise development has its own constraints and demands, which I think F# is particularly well suited for.

I’ll start with an important caveat, which is that I don’t think that the success or failure of a project depends on using a particular programming language. Much more critical are things like good communication, clear requirements, caring about the user experience, realistic expectations, and so on. If the programming language really was that important, then there would be no successful companies using PHP, Visual Basic, or JavaScript, and all jobs would require Haskell and Lisp skills!

Nevertheless, having said that, I do think that the choice of programming language has an effect on productivity, maintainability, and stability, and that’s what I’m going to talk about in this post.

The characteristics of Enterprise Development

So what are some the key characteristics of “enterprise” development?

Software development is not the focus of the business

In an “enterprise”, software is generally treated as a tool; a cost center rather than a profit center. There is no pressure to have the latest technology, or to hire the best developers, or (sadly) to invest in training.

This means that being “enterprise” has nothing to do with the size of the business. By my definition, Google does not do enterprise development, while a 50-person B2B company probably does.

This also means that companies that develop in-house software to gain a competitive advantage, like FinTech companies, don’t count as “enterprise” either.

Projects are business-centric rather than technology-centric

The goal of enterprise development is generally to support business workflows rather than to implement a specific set of technical requirements. At the most basic level, typical enterprise software just moves data around and transforms it. This sounds trivial and is often looked down on as not “real programming”.

But business workflows involve humans, and any time humans are involved you will always have complexity. Implementing an efficient map/reduce algorithm or optimizing a graphics shader might be tricky, but possibly not as tricky as some business workflows! This 30-year old quote about COBOL sums it up well:

The bias against the problem domain is stated explicitly in [a] programming language textbook, which says that COBOL has “an orientation toward business data processing . . . in which the problems are . . . relatively simple algorithms coupled with high-volume input-output (e.g. computing the payroll for a large organization).”

Anyone who has written a serious payroll program would hardly characterize it as “relatively simple.” I believe that computer scientists have simply not been exposed to the complexity of many business data processing tasks. Computer scientists may also find it difficult to provide elegant theories for the annoying and pervasive complexities of many realistic data processing applications and therefore reject them. - Ben Shneiderman, 1985

Sadly, enterprise development has never been attractive.

Enterprise projects often have a long life

It’s not unique to enterprise development, of course, but it’s common that enterprise software projects live a long time (if they survive childhood). Many projects last five years or more – I am personally familiar with one that started in the 1970’s – and over the lifetime of a project, many developers will be involved. This has a couple of corollaries:

- The majority of the project lifecycle is spent in so-called “maintenance”, a misleading term for what is basically low-speed evolution (with the occasional high-speed panic as well).

- If you are a developer working on a long-lived project, most of the code will not have been written by you, nor even by anyone currently on your team.

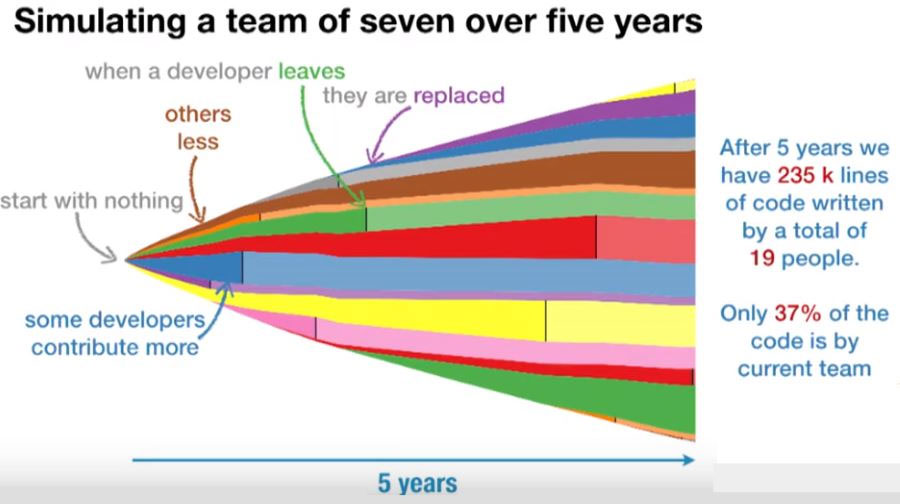

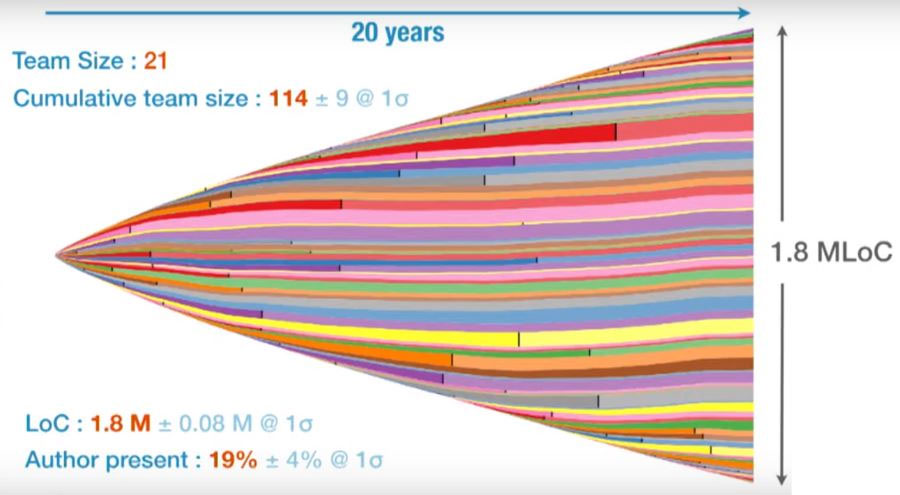

There is a very interesting talk by Robert Smallshire in which he simulates code generation for different size teams over different time periods. So, for example, after five years, the current team will generally only have contributed 37% of the code.

For a bigger team over a longer period, the contribution % can drop even lower.

Yes, these are simulations, but they ring true in my experience.

Enterprise project managers have a low tolerance for risk

As a result of all these factors, project managers tend to be risk averse and are rarely early adopters – why break something that’s already working?

As the saying goes “process is the scar tissue of organizations”. Stability is more important than efficiency.

However, new environmental conditions occasionally arise which force change on even the most conservative businesses. For example, the newfangled “intranet” and “internet” in the 1990’s scared a lot of people and had a lot to do with the rise of Java and VisualBasic/ActiveX. Here’s what the hype looked like back then:

- From 1996: “As Netscape and Microsoft battle for Net dominance, both Java and ActiveX are key pieces on the board.”

- From 1997: “Prior to Java, there was no Internet programming language.”

Less than 10 years after those articles were published, the dominant enterprise programming languages had indeed changed to Java and C#.

Thanks to mobile apps and the rise of the cloud, I think we’re in the middle of another era like this, where enterprises are willing to risk new technologies so as not to get left behind. The challenge of course, is how to adopt new technologies without major disruption.

What is important when choosing an enterprise language?

So how does all this affect choose a programming language and its associated ecosystem, from a project manager’s point of view?

It should be enterprise-friendly

A project manager is not just choosing a programming language, they’re also committing to the ecosystem around the language, and the future support for that ecosystem. As noted above, enterprise development is not about being on the bleeding edge. Rather, if the ecosystem has support from an enterprise-friendly company like Microsoft, Oracle or Google, that is a big plus.

Also, from the enterprise manager’s point of view, it’s critical that the language and its ecosystem have deep support for enterprise databases (Oracle, Sql Server), enterprise web servers, enterprise authentication (AD, LDAP), enterprise data formats (XML) etc. It’s unlikely that support for the latest hotness will be their primary concern.

It should be future-proof

Given the longevity of enterprise projects, we want to make sure that the ecosystem and tooling will still be around and supported in, say, 10 years. If and when new platforms come along, you shouldn’t have to throw away all your code.

It should be flexible

And if you’re going to commit to an ecosystem, you’d ideally want to use it in as many different situations as possible (e.g. desktop apps, server apps, web apps) and different target platforms (Windows, Mac, Linux, mobile, etc).

It should make maintenance easy

Since the members of the team will probably rotate over the lifetime of the project, and most code will not be written by the current team, the dominant concerns are things like:

- Comprehension: How easy is it to understand code that a previous team member wrote?

- Productivity: Can we add new features quickly and safely?

- Safety: If a change or refactoring is made, can we be confident it won’t break anything?

Choosing an enterprise language, part 1

With these requirements in place, we can use them to reduce our language choices.

-

For easy maintenance and safety most people agree that you need a statically-typed language. When you have a large code base with 10’s or 100’s of people working on it over the years, statically-typed languages support better refactoring, and compile-time errors can help prevent bad code from going into production. Sorry, PHP, Python, JavaScript and Clojure!

Here’s John Carmack on this topic:- The best of intentions really doesn’t matter. If something can syntactically be entered incorrectly, it eventually will be. And that’s one of the reasons why I’ve gotten very big on the static analysis, I would like to be able to enable even more restrictive subsets of languages and restrict programmers even more because we make mistakes constantly. - John Carmack, 2012

- Software development is not the focus of the business implies that the emphasis is on stability and productivity, rather than, say, performance. This means that an enterprise programming language should not allow potentially dangerous actions such as control over memory and pointer arithmetic. Even if it can be done safely, as in Rust and modern C++, the effort to squeeze out the extra performance is generally not worth it. Letting the garbage collector take care of everything frees up time to focus on other things.

-

It should be enterprise-friendly so it’s no surprise that the favorites are:

- Java (and languages on the JVM that can piggy-back off the Java ecosystem).

- C# (and other languages in the .NET ecosystem).

- Go also gets some points here because of Google supports it, and you can be confident that critical enterprise libraries will be available.

So, far no surprises. We have come up with the usual suspects, Java and C#.

If this was 2008, we’d be done. But it isn’t, and we’re not. In the last decade, there has been an explosion of new languages which are strong contenders to be better enterprise languages than C# and Java. Let’s look at why.

The rise of functional programming

Functional programming is the new hotness right now, but regardless of the hype, most modern programming languages are introducing FP-friendly features that make a big difference to software quality:

- Higher-order functions replace heavyweight interfaces in many cases (the C# LINQ and Java streams libraries would not be possible without them).

- Different defaults, such as immutability by default and non-null by default. Having these as the default makes maintenance and code comprehension much easier, because deviations from these defaults are explicitly signaled in the code.

- Making effects explicit is emphasized by the functional programming community. This includes such things as a Result type for explicit error handling, and moving I/O and other sources of impurity to the edges of the application (as seen in the functional core/imperative shell and Onion Architecture approaches).

- Finally, and most importantly, FP-influenced languages have algebraic data types. That is, not just records/structs, but also “choice” types (aka sum types or discriminated unions). In my opinion, these are essential for effective domain modeling. Of I course, I would say that, as I wrote a book on the subject, but I’m not alone in this view.

If we look at languages which support these features, we end up with the mainstream statically-typed FP languages (Haskell, F#, OCaml) and the more modern FP-influenced languages: Swift, Scala, Kotlin, Rust, TypeScript, etc.

As I said above, the rise of new technologies such as serverless means that enterprises will be willing to switch to these FP-influenced languages if they can provide a competitive advantage (which I think they do) and if the switch can be made with minimal disruption (which depends on the choice of language).

The danger of too much abstraction

Some FP languages (Haskell and Scala in particular) support some features that allow high levels of abstraction. Some people like to quote Dijkstra here:

“The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise” – E.W. Dijkstra

That’s great, but I believe that in the specific context of enterprise development, too much abstraction can cause problems. If used too freely, it requires that all developers working on a project need to have the same understanding of the “new semantic level”, which is a burden on training and employability. All it takes is for one person to have too much fun with category theory in the code, and the code is rendered unmaintainable for everyone else.

That is, just as you can shoot yourself in the foot with low-level features, you can also shoot yourself in the foot with high-level features as well. For an enterprise language, we need to trim the top-end of the language capabilities as well as the bottom-end, and encourage an “only one way to do it” approach as much as possible.**

So I’m going to penalize Haskell and Scala at this point for being too easy to abuse.

** One of reasons people like Go or Elm as languages is because they are restrictive. There is a standard way of doing things, which in turn means that reading and maintaining someone else’s code is straightforward.

But how much abstraction is too much?

Are generics too advanced? 15 years ago, perhaps. But today it’s clear that it’s a mainstream feature. (The golang designers disagree!)

But how about lambdas? How about monads? I think that most FP concepts are on the verge of being mainstream now, and in ten years time will be commonly accepted, so it’s not unreasonable to have a language that supports them.

For me, in 2018, the “just-right” level of abstraction is that found in ML languages like OCaml and F#. In 10 years time things may be different, and we may be able to adjust the acceptable level of abstraction upwards.

However, I’m not convinced that more abstract, mathematical style programming (a la Idris, Coq) will ever be commonplace in the enterprise, due to the variation in employee skills. Yes, this could be solved with better training, or a certified-software-engineer qualification, but I’m not holding my breath.

Choosing an enterprise language, part 2

If we then filter these newer languages by the “enterprise” criteria above we end up with the FP-influenced languages that support .NET and the JVM, namely:

- F# on .NET

- Kotlin on the JVM.

- I’m also going to add in TypeScript as well, as it is very well supported and meets the “enterprise” criteria.

To summarize the “why not language X” objections again:

- C# and Java – These are OK, but F# and Kotlin respectively have better defaults (immutability), better support for effects, and better support for algebraic data types.

- Swift – It’s well-supported within the Apple ecosystem but shows no signs of spreading into enterprises in general.

- Ceylon – Kotlin has more momentum.

- Haskell – Yes, Haskell does enforce purity rigorously, which is great, but that’s not the only component of programming. More importantly, there is no gradual migration path to Haskell – you are thrown in the deep end. That might be great for learning FP but is not suitable for enterprise, IMO.

- Scala – Too many different ways of doing things is a disadvantage, I’m afraid. Kotlin is more enterprise-friendly.

- OCaml – If you don’t need enterprise support, then OCaml is an excellent choice. But if you do, F# would be more applicable.

- Go – Great for some things but not recommended for enterprise due to weak support for domain modeling with types.

- Elm/Purescript – Front-end only right now.

- Reason ML – Front-end only right now. Also, why not just use OCaml?

- C++/Rust – If you don’t need performance, a GC’d language is easier to work with.

- Erlang/Elixir – Great for high uptime, but not enterprise-friendly.

- PHP/Python/Ruby/etc – I like Python a lot, but maintainability goes out the window when you have more than 10K LoC. As I said above, statically-typed languages are the only way to go for large projects.

What about higher-kinded types? What about type classes? What about GADTs?

Oh dear, none of the three finalists support them right now. I’ll let you judge whether this is a deal-breaker for enterprise development.

Picking a favorite

The three languages left (F#, Kotlin and TypeScript) are all good choices, they’re all open-source, cross platform, and enterprise friendly.

If you’re already using the JVM, then obviously Kotlin provides the best migration path. Similarly, if you’re using Node on the backend, then TypeScript is good (although trusting npm packages might be a problem).

But if you’re doing greenfield development (or if you are already on .NET) I believe that F# has the edge (and this is where I might be a bit biased!)

- It has excellent support for low ceremony domain modeling.

- It is functional-first, preferring functions and composition as the primary development approach.

- Immutability really is everywhere – it’s the default for algebraic types and collections.

-

It has a wide range of capabilities. For example:

- You can build microservices that support millions of customers. Here’s how jet.com did it.

- You can write JavaScript in F# with Fable. For example, the F# plugin for VS Code, called Ionide, was built in F# and converted to JS this way.

- You can develop full stack web apps (sharing the code between the front and back end) with the SAFE stack or WebSharper.

- You can build mobile apps with the Fabulous library using an Elm-like approach.

- You can build desktop apps with XAML or WinForms or Avalonia.

- You can create lightweight scripts, such as build- and deployment pipelines.

- Another nice use for scripts is browser UI testing.

- And of course you can do data science.

Of course, Kotlin can do some of these things and TypeScript some of the others, but I think that F# has the most breadth overall.

Extract from ScottW's note: https://fsharpforfunandprofit.com/posts/fsharp-is-the-best-enterprise-language/

Discover how we can help you

Please leave us your question and one of our assistants will contact you asap.